Ratnapith College, Chapar, Assam, India

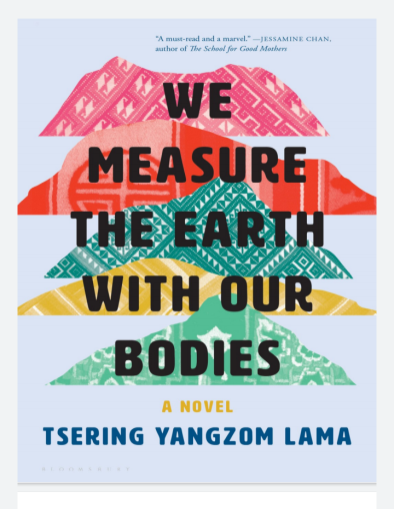

We Measure the Earth with Our Bodies | Fiction | Tsering Yangzom Lama

Bloomsbury Publications (2022) | ISBN-10: 9356402256

Paperback | pp 368 | Rs. 464

An intriguing coalescence of histories, realities, culture and emotion

We Measure the Earth with Our Bodies, the debut novel of Tsering Yangzom Lama, is a gripping tale of deprivation, displacement and distorted representation that grapples with raw emotions and harsh realities. Lama also presents thought-provoking instances and brings out the rich culture and traditions of the Tibetans through the narrative, the characters and also through the arduous journey which the characters are forced to embark upon.

The novel opens in the wake of the Chinese annexation of Tibet in the 1950s when the Dalai Lama, guided by the divination of the Nechung Oracle, escaped to India as the ancient prophecy heralds, “When the iron bird flies and horses run on wheels, the People of Snows will be scattered like ants across the face of the earth.” Following which two Tibetan sisters Lhamo and Tenkyi along with their parents and a few of the villagers were compelled to flee their homes guided by their mother who was an oracle, and after an arduous journey through hills and caves, they landed in a refugee settlement in Nepal never to return home again. From the very first chapter of the novel, we can get a glimpse of Tibetan customs and traditions, divinations and oracles. Even the title of the novel resonates with a holy tradition- “(a) pilgrim who had even travelled across all of Tibet, from east to west, lying down and rising, over and over until he reached the yearly Kalachakra prayers in India… To measure the earth with my body, to know our country with my own skin. It seemed like the only way to fathom such a land”. The idea of land here becomes symbolical of the loss of homeland coupled with the loss of identity and traditions which become a prominent theme of the entire novel. The novel articulates the atrocities the soldiers had subjugated the Tibetans to – of Chinese soldiers tossing and mocking the oracles, tossing aside the prayer flags, forcing the Tibetans to pulverise the holy statues and relics of the monasteries and making bullets out of them- “They will kill us with our own gods”.

The portrayal of the Nepalese refugee settlement depicts the struggle to survive, work and gain an education and, to quote Tenzin Tsundue, “none of them can ever empathise with the plain simple fact that I have nowhere to call home and in the world at large all I’ll ever be is a ‘political refugee’.”

Tenkyi the bright student of the refugee settlement is sent to Delhi and she eventually emigrates to Canada with Dolma. Dolma aims to pursue scholarship in Tibetan culture and history and that is where they are reunited with an idol, the ku of the Nameless saint who is their spiritual guide and it is believed that it was only with his guidance that they were able to safely escape from Tibet. The ku plays a crucial role in the entire novel, overlaying religion and mysticism and connecting the lives of various characters, including that of Tenkyi, Dolma, Lhamo and Samphel. When Lhamo carries off the ku from the office, walking in the footsteps of a popular legend, she hands it to Samphel who she believes is the rightful owner of the ku. Out of disparity, Semphel deals with antiques and is forced to sell the ku only for Dolma and Tenkyi to retrieve it again. The act of defiant retrieval and preservation of the ku by Lhamo and by Dolma and Tenkyi echoes the pain and struggle of the Tibetans in upholding their culture and traditions in a foreign land- “Before we can reply, he (the ku) says, I have traversed the earth to be with you, to tell you one thing: Just like you, I am in anguish. Like you, my insides twist and jerk, a bird unable to take flight. My body, like yours, is worn through and could snap at any moment. But I will not break because I can endure so much more. I can take your agony, your hunger, your nightmares. I can bear all the misery you have carried since your birth. Through my face and my body, I will reflect your torment back to you. And you will know, finally, that you are not alone”.

Dolma’s interaction with her professors also highlights the perception of the West towards the Orient- “Then my eyes fall on a statue of a bronze Buddha—Thai, it seems, from the pointed spire of hair and the sleekness of his body. There’s something comical about his presence in the room, standing far off in the corner, overlooked by everyone, his right hand raised in the mudra of bestowing protection”. The ku having religious and cultural connotations to the Tibetans becomes only a vestige of the museum. Thus, the narrative challenges the Western perception, conceptions and misconceptions of the Orient-

The ku is seen as a team- “To lay a hand on a rock and recognize verses of metaphysics. To grind an herb and discover a moment of wisdom that unleashes entire teachings” and it is only when she is surrounded by people alien to and ignorant of her emotions and tradition that she realises the grave misrepresentation which Tibet along with its vicinities are a victim to. Thus, the narrative challenges the Western perception, conceptions and misconceptions of the Orient- “I had felt washed in shame, imagining that this was our image in the West. It all seemed like a horrible misunderstanding— as though someone far away had tossed together a dozen fabricated characteristics from India, Nepal, China, and Tibet, picked randomly across centuries of history, shook them around in a box, and let the pieces fall out”.

The author follows a lucid and engaging style of writing and even when the narrative appears to be brusque at times, it provides a thorough insight into their issues, customs and traditions. The narrative is polyphonic in nature and the multi-voicedness enables one to comprehend the narrative by acknowledging not only the emotive pain and loss of culture and identity but also highlighting the Tibetan oracular tradition, Tibetan refugees in Nepal, Tibetan antiquities trade, etc. which form an important part of their life, history as well as the narrative. The protagonists of the novel undertake not only the physical journey but also embark on a spiritual as well as existential quest- “Every line from my childhood, every answer to the question “Who are you?” is ready at my lips. We are asylees. We are refugees. The Chinese government took our land and killed our people, 1.2 million souls. Our documents are flimsy— just laminated scraps of common paper, not embossed leather passports like yours—and considered illegitimate by most nations. Please overlook our present degradation. You should have seen us before the invasion when our country had kings and gods and an unbroken thread of history from a time before time”. The journey, therefore, becomes a metaphor for the quest and their suffering- “People find our culture beautiful,” I say. “But not our suffering. No one wants to put that in a glass case. Nobody wants to own that.”

I would say that it was a well-executed plot which opens up avenues of viewing the narrative under memory studies and trauma studies, especially under the framework of postmemory theory which explores the transmission and impact of traumatic experiences across generations. Moreover, the narrative also voices an ecocritical concern when Tenkyi observes garbage and seagulls being tossed around in the lake’s erratic wind’ and that is when she exclaims, “The lake and sky look like soot, but the sun is rising somewhere behind the clouds… A few geese waddle by, saying nothing, defecating along the banks. Even in the grey light, I see their blackheads hiding their black eyes. The people on the television are right. The earth is not well”.

Like the ku of the Nameless saint, the novel can be seen as a talisman- a narrative which unleashes traditions weaved in the tapestry of fiction tinged with history. I strongly believe that the novel is a fascinating chronicle of Tibetan life, people and history, and highlights the contemporary issues which they are dealing with- “If I were an insect, I could fly back and forth all day. But perhaps this is the point. After all, what better way is there to demonstrate our lack of power? Yes, this is how you break a heart. With a wire fence that shows everything that cannot be touched. While the wind sweeps the expanse, while the rain clouds roam, free as ever. We get a glimpse and nothing more”. The novel resonates with the loss of home and even perpetuates the sense of losing a home which one has never been- “I feel a kind of stability. This is a familiar threshold, facing in opposite directions: Toward a country, I cannot truly enter. And back to a world that cannot be my home. Forward or back, no step makes sense. So I must remain between two realms. This fence under my feet is a tightrope I can never leave”.

Bionote:

Paddaja Roy is an Assistant Professor in the Department of English, at Ratnapith College, Chapar, Assam. She has done her specialisation in Translation Studies and she has also been engaged as a content curator. Her area of interest includes Northeast Writings, Media Studies, Indian Writing in English, Creative Writing and Oral Literature. She can be reached at paddajaroy@gmail.com

ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0009-0009-2226-9645

Open Access:

This article is distributed under the terms of the Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/) which permits any use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission.

For more information log on to https://thetranscript.in/

Conflict of Interest Declaration:

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest about the research, authorship and publication of this article.

© Author